The career of Allan Kardec (Part II)

THE CAREER OF ALLAN KARDEC (PART II)

Steve Hume

The book attained a wide readership from all classes of society.[28] Some were attracted to the spirits' statements in relation to scientific matters and it is astonishing how few of the spirits' 'scientific' statements appear anachronistic today. In fact, some of the answers to Rivail's questions could be interpreted as being remarkably ahead of their time. One such example was Rivail's question 'Does an absolute void exist in any part of space?' which received the reply:- 'No, there is no void. What appears like a void to you is occupied by matter in a state in which it escapes the action of your senses and of your instruments.'[29] This statement (given in the1850's), to the effect that seemingly empty space is really full of matter, has only received confirmation quite recently by the discovery of what is termed the 'quantum vacuum',[30] and was given shortly after the spirits had also casually announced that '...what you term a molecule [or, perhaps, 'particle' or 'atom'] is still very far from being the elementary molecule'.[31] This latter scientific fact would not be confirmed until J.J. Thomson discovered the electron almost half a century later. However, The Spirits' Book drew most converts to Spiritism from the ranks of the French working classes,[32] perhaps for the simple reason that the spirits had nothing good to say about the inequity that was, and still is, inherent in human society. In fact, the Spiritist attitude towards this may is summed up in the spirits' answer to Rivail's question 'Which amongst the vices, may be regarded as the root of the others?', which received the reply:- 'Selfishness, as we have repeatedly told you; for it is from selfishness that everything evil proceeds. Study all the vices...Combat them as you will, you will never succeed in extirpating them until, attacking the evil in its root, you have destroyed the selfishness which is their cause. Let all your efforts tend towards this end; for selfishness is the veritable social gangrene. Whoever would make, even in his earthly life, some approach towards moral excellence, must root out every selfish feeling from his heart, for selfishness is incompatible with justice, love, and charity; it neutralises every good quality.'[33]

This meant that the Spiritist ethos became anchored on the central principle of charity, not only in relation to material goods, but also to just about everything else, including the practice of mediumship. But the Kardec spirits also denounced sexism, racism, capital punishment, slavery and every other form of social injustice and prejudice as being contrary to Divine Law; but recommended freedom of thought, freedom of conscience, equality and tolerance. In effect, what was being advocated was a program of social reform, framed within a 'spiritual' context, that was light-years ahead of the pious conservatism of the Catholic Church. The foregoing point also represents what is perhaps the greatest difference between the portrayal of Spirit life given by the Kardec spirits and the account given by others since. Rivail only seems to have been interested in the great moral and scientific concerns of the human race and framed his questions accordingly. So The Spirits' Book contains no mention of Spirit houses etc. that are a familiar feature of the literature of Spiritualism. The subject matter is almost wholly oriented towards the effect that moral behaviour has upon the individual, both on Earth and in the hereafter.

Encouraged by the success of The Spirits' Book, Rivail decided to start a monthly journal. Unable to obtain financial backing for this venture he sought the advice of his guides through the mediumship of Miss E. Dufaux and was told that he should fund the journal himself and not worry about the consequences.[34] Accordingly, the first issue of La Revue Spirit appeared on January 1 1858 and, as with The Spirits' Book, its success surpassed Rivail's expectations. He also founded The Parisian Society of Psychologic Studies. But his work for Spiritism had only just begun. He published The Mediums' Book in 1861 which dealt solely with the Spirits' views on the development and uses of mediumship itself. For this and the other works that would follow, he used even more mediums than for The Spirits' Book but the employed the same method of presentation i.e., his questions followed by the spirits' answers which were supplemented by his own comments and observations.

Rivail quickly became regarded as the foremost authority on mediumship in France and was held in awe in by the Spiritists in his home town of Lyon, so much so that, in 1862, he had to plead with them not to waste money on honouring him with a lavish banquet as they had done the year before.[35] Anna Blackwell mentions that he was constantly visited by those 'of high rank in the social, literary, artistic, and scientific worlds' and he was summoned by the Emperor Napoleon III, several times to answer questions about the doctrines of Spiritism.[36] But, of course, the rapid rise of Spiritism did little to endear Rivail, or Spiritists in general, to certain sections of the French Establishment and even some Spiritists who came to resent his influence on the movement. This opposition, particularly from the Church, could hardly have come as any surprise to Rivail, but one would imagine that that rom within Spiritism would have been particularly distressing to him. In fact, he had been warned of both, and much else besides, by the spirits in 1856, before he had any idea that he would become such a prominent champion of the Spiritist cause:[37] 'Terrible hates will be incited against you; implacable enemies will plot your downfall. You will be exposed to calumny and treachery, even from those who seem most dedicated to you. Your best works will be contradicted and banned.'[38]

The communication was given, appropriately enough as it transpired, by a communicator who called himself the 'Spirit of Truth'. Predictably, the Catholic church, both in France and elsewhere, was particularly eager to discredit both Spiritism and Rivail. David J. Hess, in Spirits and Scientists: Ideology, Spiritism and Brazilian Culture, mentions a number of actions taken by the Church against the new movement which it regarded as being worse than Protestantism.[39] Before the publication of The Spirits' Book in 1856, the Holy Office, under Pope Pius IX, had prohibited mediumship and 'other analogous superstitions' as 'heretical, scandalous, and contrary to the honesty of customs'. But in 1861 the Bishop of Barcelona took more direct action. He ordered an auto-da-fe (act of the faith) known as the Edict of Barcelona, against three-hundred Spiritist books, including many by Rivail, that were confiscated and burnt in public.[40] However, the Bishop's actions did nothing more than stir up French nationalism and contribute to the further growth of Spiritism in both France and Spain. Hess adds that when the Bishop died nine months afterwards, his repentant spirit manifested through several French mediums begging for Rivail's forgiveness which was, apparently, granted. In France, the dean of the Faculty of Theology of Lyons began public education courses against Spiritism and Mesmerism in 1864 and Spiritism was widely branded as a form of demon worship in writings by clergymen.

Rivail accused the Church of deliberately inciting hatred against Spiritists:- 'From the pulpit, we Spiritists have been called enemies of society and public order...In some places, Spiritists were censured to the point of being persecuted and injured on the streets, while the faithful were forbidden to hire Spiritists and were warned to avoid them as they would avoid the plague. Women were advised to separate from their husbands...Charity has been refused to the needy and workers have lost their livelihoods, just because they were Spiritists. Blind men have even been discharged, against their will, from some hospitals because they would not renounce their beliefs.'[41]

As with Spiritualism in America and Britain, certain sections of the French scientific establishment also reacted with hostility to the spread of Spiritism. Hess mentions that a Dr Dechambre, a member of the Academy of Medicine, published a critique of the movement in 1859, and also cites reports of insanity, allegedly caused by Spiritism, that had started to circulate by 1863.[42] There was even a French equivalent to the theory, which originated in America, that spirit raps were produced by the cracking of the knee and toe joints. The French variation on this theme was presented to the Academy of Medicine by a surgeon, M. Jobert, who attributed the noises to skilful cracking of the short tendon of the muscle of the instep.[43] However, in accordance with the spirit prediction just mentioned, Rivail also faced bitter opposition from within Spiritism itself. Writing of the accuracy of the 'Spirit of Truth's' warning eleven years later he complained:- 'The Societe Spirite de Paris (Spiritist Society of Paris) has been a continuous focus of intrigues, devised by those who declared loyalty and friendship to me, but who slandered me in my absence. They said that those who favoured my work were paid by me with money I received from Spiritism.'[44] I have already mentioned above that Rivail's endorsement of the doctrine of reincarnation had caused a certain amount of friction with the followers of the mesmerist, Alphonse Cahagnet and it is easy to imagine that the prominence he had achieved so rapidly in the Spiritist movement would excite jealousy in others. After all, few human endeavours, even those supposedly dedicated to 'spiritual' motives, are free from rivalry and controversy. It would appear that, far from being grateful to Rivail for the wider exposure and support that he had gained for Spiritism, some Spiritists resented his influence.

It would not be unreasonable to assume that, in Rivail's case, a fair amount of this acrimony was the result of the way in which he viewed mediumship. As we have already seen, he appears to have come to the Spiritist movement as a relatively disinterested outsider with no emotional attachment to any particular idea about the subject. Once he had reached the conclusion that the communications were, indeed, the work of discarnate entities he may therefore have been more suited to judging these objectively than some individual mediums and their followers who, then as now, must have been occasionally prone to what could be termed 'My Guide Knows Better Than Your Guide Syndrome'.

I have given an outline of the way in which Rivail judged the worth of spirit statements of a philosophical nature above. But he also adopted criteria for deciding whether or not a communicator was likely to be the person that they were claiming to be.[45] Working according to the famous principle of 'like attracts like' on the basis that every human being has some imperfection in their moral nature, he took it for granted that even the best mediums (especially writing mediums) could,at some point in their careers, fall prey to spirit personalities who would try to lead the medium astray by borrowing some revered name, thus flattering the medium's vanity to gain acceptance for the most ridiculous statements. In cases such as this, where good evidence of identity, as such, might be difficult or impossible to obtain, he recommended that the communication be judged on whether or not the sentiments expressed, and the manner of their expression, were in general accordance with what one would expect from the personality concerned. And, even if this condition was met, he only accepted (at best) the 'moral probability' that the identity was correct. The Mediums' Book, published in 1861, as the title suggests, is wholly concerned with mediumship itself. It is really a handbook for the development and proper use of the gift that is, ostensibly, written from the communicating spirits' point of view; needless to say these were all claimed to be highly advanced personalities, some well-known, others anonymous. The material for The Mediums' Book, and the others which followed, was drawn largely from automatic writing mediums at Rivail's 'Parisian Society For Psychologic Studies' but it also included the work of others who sent communications from elsewhere in France and abroad. [46] As with The Spirits' Book, Rivail claimed to be presenting a view on the various subjects dealt with that could be considered authoritative because it was drawn from a wide variety of independent sources that broadly agreed with each other...a sort of consensus of opinion amongst 'advanced' spirits.

Every conceivable aspect of every type of mediumship and spirit manifestation is dealt with in The Mediums' Book (even charlatanism receives a chapter of its own) but Rivail devoted special space to the effect that the moral characters and preconceived ideas of mediums themselves may have upon the ability of spirits to communicate effectively. He identified twenty-six considerations that should be taken into account in judging the worth of communications and gave examples of some that could not reasonably be attributed to the author claimed.[47] A good example is the following:- 'Go forward, children, march forward with elated hearts, full of faith; the road you follow is a beautiful one...'[48]

This communication, which continued in similar platitudinous vein at some length, was signed with the name 'Napoleon', and it drew the following comment from Rivail:- 'If ever there were a grave and serious man, Napoleon, while living, was such an one; his brief and concise style of utterance is known to all, and he must have strangely degenerated since his death, if he could have dictated a communication so verbose and ridiculous as this...'.[49]

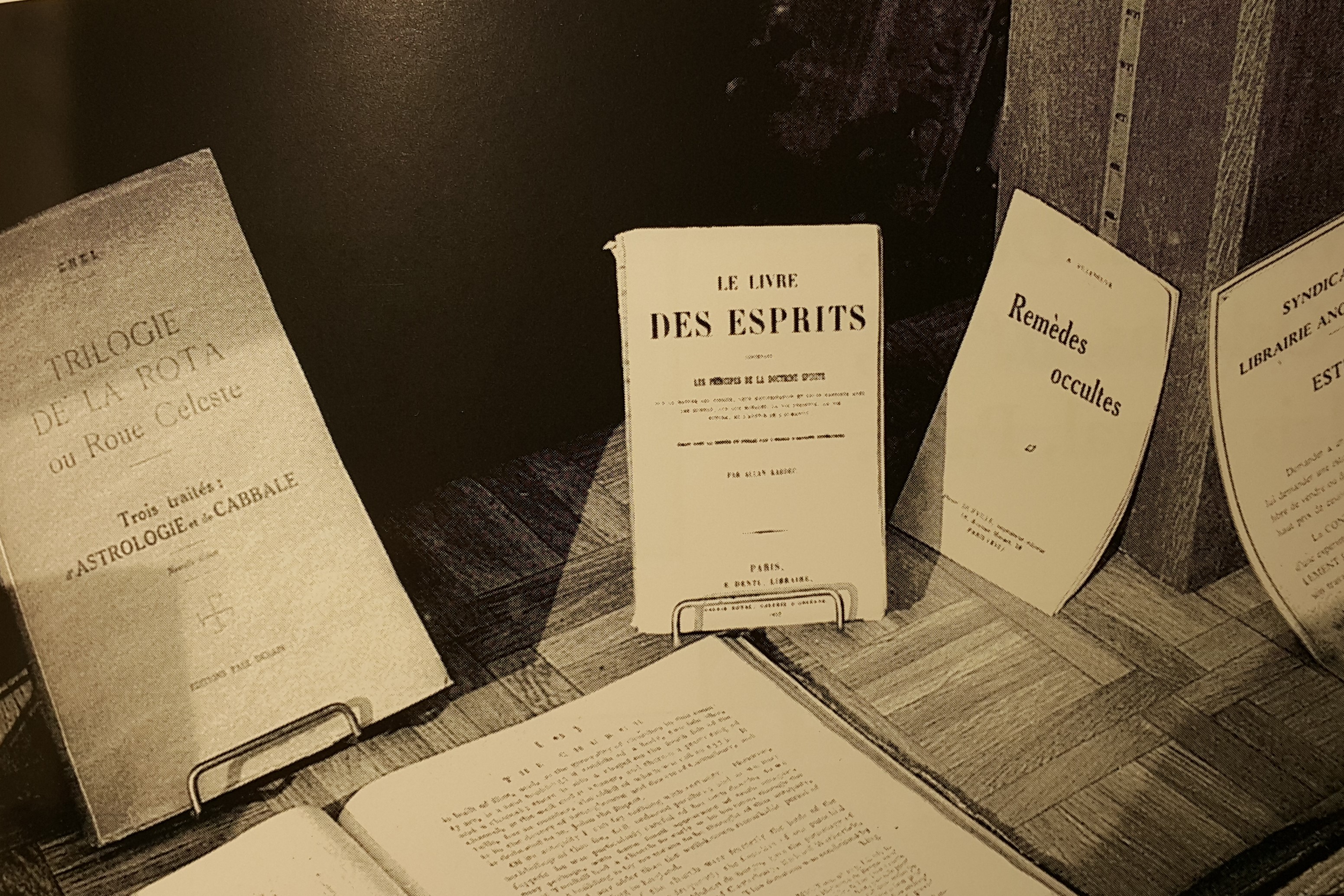

This attitude must surely have offended certain mediums and Spiritist groups who were in the habit of accepting communications such as this at face value. The fact that Rivail referred to such people with barely veiled despair in a chapter on the dangers of Spirit obsession,[50] indicates that he was only too aware of the ridicule that they were capable of provoking from ever eager critics. His reference to 'enemies' of Spiritism 'those who pretend to be its friends in order to injure it underhandedly' and the recommendation that Spiritist societies be kept small because 'such persons find it far more easy to pursue their aim of sowing discord in large assemblies than in little groups of which all the members are known to each other',[51] also suggests that he was worried that the movement contained people who he considered to be wrongly motivated. Nonetheless, The Mediums' Bookcomplemented The Spirits' Book perfectly in that it provided a sound guide through the many difficulties that can arise during the practice of mediumship. It would be joined in 1864 by The Gospel According to Spiritism which contained the spirit teachers' comments on the New Testament. This trio of books is regarded by Spiritists as being the cornerstone around which the modern movement has been built. However, Rivail would publish two further major works under the name 'Kardec': Heaven and Hell (1864) which was based upon the spirits' comments about the real nature of these as mental/spiritual states; and Genesis (1867) which showed 'the concordance of the spiritist theory with the discoveries of modern science and with the general tenor of the Mosaic record as explained by spirits'.[52] He also published two short treatises entitled 'What is Spiritism' (1859) and 'Spiritism Reduced to its Simplest Expression' (1860) which was a dialogue between Rivail and three critics of Spiritism...'The Critic', 'The Sceptic' and 'The Priest'.

In 1867, with the publication of Genesis, Rivail completed the series of books that today are regarded by the more evangelically minded Spiritists as comprising 'the third revelation' of God to humankind, the first being the teachings of Moses and the second those of Jesus.[53] However, Rivail himself would probably have balked at this as he had merely claimed that Spiritism, or the modern explosion of spirit communication, was the third revelation. But, as with almost every other aspect of the 'Kardec' teachings this idea had come not from himself, but from the Spirit communicators, one of whom expressed it most succinctly in The Gospel According to Spiritism:- 'Moses showed humanity the way; Jesus continued this work; Spiritism will finish it.'[54]

Rivail himself wrote of this aspect of Spiritism:- 'The Law of the Old Testament was personified in Moses: that of the New Testament in Christ. Spiritism is then the third revelation of God's law. But it is personified by no one because it represents teaching given, not by Man but by the Spirits who are the Voices of Heaven, to all parts of the world through the co-operation of innumerable intermediaries. In a manner of speaking, it is the collective work formed by all the Spirits who bring enlightenment to all mankind by offering the means of understanding their world and the destiny that awaits each individual on their return to the spiritual world.'[55]

References

[28] David J. Hess, ibid., p.62.

[29] Allan Kardec (b), The Spirits' Book (London: Psychic Press Ltd, 1975), p.13.

[30] Robert Mathews writing in Focus magazine, December 1997, pp.10-11.

[31] Allan Kardec (b), p.12.

[32] See 5.

[33] Allan Kardec (b), p.354.

[34] Allan Kardec (a), p.196.

[35] See 6.

[36] Anna Blackwell, ibid., p.17.

[37] Allan Kardec (a), pp.196-197.

[38] Allan Kardec (a), p.197.

[39] David J. Hess, ibid., pp.67-68.

[40] Allan Kardec (a), p.100.

[41] Allan Kardec (a), p.99.

[42] David J. Hess, ibid., pp.77-78.

[43] Allan Kardec (c), The Mediums' Book (London: Psychic Press Ltd, 1977), p.35.

[44] Allan Kardec (a), pp.197-198.

[45] Allan Kardec (c), pp.296-318.

[46] Allan Kardec (c), translator's note by Anna Blackwell, p.417.

[47] See 8.

[48] Allan Kardec (c), p.441.

[49] See 11.

[50] Allan Kardec (c), pp.277-295.

[51] Allan Kardec (c), p.407.

[52] Anna Blackwell, ibid.,p.15.

[53] David J. Hess, ibid., p.18.

[54] Allan Kardec (d), The Gospel According to Spiritism (London: The Headquarters Publishing Co.

Ltd, 1987), p.28.

[55] Allan Kardec (d), p.25.

Source: The Spiritist Messager, 6th year - Number 21 - distributed: November 1999